Life in Motion: An Interview with Curator Tamar Hemmes

The Tate Liverpool have previously run exhibitions that innovatively pair artists of different mediums together, to forge connections between their work. For example, in 2017 “Portraying A Nation: Germany 1919 -1933” compared the work of Weimar artists Otto Dix and photographer August Sander. In their latest exhibition “Life in Motion” the Tate have yet again utilised their tried and tested formula, and even taken it one step further, selecting artists from wildly contrasting periods in history; Egon Schiele and Francesca Woodman. We chatted with exhibition curator Tamara Hemmes to discover more about how these artists both worked with the subject of the human body, and how viewing them together can give them new relevance to contemporary art practice.

By Emily May | Updated Apr 2 2019

Culture Calling: What was the inspiration behind Life In Motion: Egon Schiele/Francis Woodman?

Tamar Hemmes: We really started with looking at Egon Schiele. It’s 10 years since Liverpool was capital of culture, and during that year we had an exhibition of Gustav Klimt who was actually Egon Schiele’s mentor. It’s a really nice connection to have back to 2008 which was an important year for the city. We really wanted to look at Schiele’s practice in a different light, because there are a lot of exhibitions of his work but they’re always very similar, and what we were really interested in was how he has this incredible ability to show the human body. We then wanted to pair him with an artist that would highlight how relevant his approach still is in modern and contemporary practices. We chose Francesca Woodman as we have some of her work in our collection, and because we saw a similarity between the two artists. They really focus on the expressive nature of the body rather than just formal portraits.

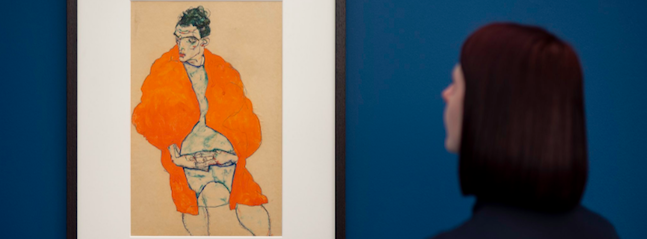

Egon Schiele, 1890-1918. Self-Portrait in Crouching Position 1913. Gouache and graphite on paper. 323 x 475 mm. Moderna Museet / Stockholm. Photo: Moderna Museet / Stockholm

Egon Schiele, 1890-1918. Self-Portrait in Crouching Position 1913. Gouache and graphite on paper. 323 x 475 mm. Moderna Museet / Stockholm. Photo: Moderna Museet / Stockholm

CC: Both artists are from wildly different contexts, Schiele from turn of the century Austria and Woodman from mid 20th Century America. What do you think is important about showing work from contrasting periods alongside each other?

TH: I think it really shows how they were both quite progressive for their time. Especially with Schiele, you see his work and realise that his approach to the human body and figure was not common for that time. He also inspired a lot of subsequent artists, for example Tracy Emin. With Francesca Woodman as well, she was working at a time when the feminist movement was very important. There was a lot happening politically in that sense, but she approaches her own body and the bodies of other women from a very personal standpoint. So, it’s really about looking at the similarities and differences between the artists, but really focusing on the shape of the body, and how their depictions of the physical body can actually convey a lot about the psychological state of the subject.

CC: Movement’s obviously really difficult to capture in still images and visual art. Can you speak a bit about how each artist achieves this sense of dynamism in their work?

TH: For Schiele, what he really focused on was unconventional poses. You see a lot of contorted bodies, with arms bent in really uncomfortable positions. If you look at Schiele’s drawings of people, his works on papers, you can also see that he shows his subjects in front of a blank background. He takes away the surroundings, which means you don’t have a point of reference for the space that the person would have found themselves in. And then what he does, especially later on in his career, is to depict women who would have been reclining, in a vertical composition. He turns the page, which makes the seem as if they’re sitting up or kneeling, and that adds a lot of movement within that composition because their centre of gravity is off, so a falling motion is created.

For Francesca Woodman it’s actually quite different, in that she was obviously working with photography. She used a long exposure on her camera, which made the background in which she shows her subjects very crisp and structured, but she’d have her model move within that exposure time so that you get a blurred image within that. It really seems like a fleeting moment.

Image Credit: Francesca Woodman, 1958-1981. Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island 1975-1978. Gelatin silver print. 109 x 109 mm. ARTIST ROOMS Acquired jointly with the National Galleries of Scotland through The d'Offay Donation with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund 2008. © Courtesy of Charles Woodman/Estate of Francesca Woodman.

Image Credit: Francesca Woodman, 1958-1981. Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island 1975-1978. Gelatin silver print. 109 x 109 mm. ARTIST ROOMS Acquired jointly with the National Galleries of Scotland through The d'Offay Donation with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund 2008. © Courtesy of Charles Woodman/Estate of Francesca Woodman.

CC: Obviously this preoccupation with movement is very reminiscent of the art form of dance. And of course, there’s the beautiful exhibition trailer which features two dancers.

TH: We don’t have any direct references to dance in the exhibition but it was definitely a very important starting point for us. Especially when you look at modern dance, there’s actually a lot of movement in there that is comparable with the forms in Schiele’s work.

CC: And are there any subthemes in the exhibition under this overarching umbrella of movement?

TH: There’s obviously always different aspects of the work that you’re looking at. For example, with Francesca Woodman, there are quite a number of works with quite a spiritual feel to them. It seems she is in between appearing and disappearing, you almost see the shadow of a figure rather than someone who’s fully in focus. She did a series called The Angel Series that was clearly looking at this sense of transitioning between different states. With Schiele we focus on things like his preoccupation with the hands as an expressive part of the human body. He felt that they were one of the ways we could really show our emotions. So we have divided the show into different sections and each one has more of a specific focus, but all the works focus on the human body.

Image Credit: Tate Liverpool via Twitter

Image Credit: Tate Liverpool via Twitter

CC: One way Schiele depicts the human body is by looking at the female figure through an erotic lens. But the exhibition states it is trying to go beyond these sexual depictions. What do you think is the difference between these more erotic and hence controversial depictions, and the rest of his work such as his self-portraits?

TH: The interesting thing is that there’s not a clear difference between the two, but it’s more that you can just tell that he’s interested in depicting the body in all different states. There’s quite a logical explanation for him doing self-portraits rather than using male models; he was struggling financially for a long period during his career. He also had quite a lot of street children hanging around his studio, and he was really interested in how they weren’t effected by societal constraints, because Vienna at the time was very conservative. With it being so conservative, it is interesting that he was exploring female sexuality. It’s been said quite a lot that Schiele is a feminist. I don’t know if I would go that far, but it’s quite interesting to see how he approaches sexuality in his work in a very direct and matter of fact way.

CC: And do you still have some of these erotic works on display despite the show’s aim to move in a different direction?

TH: Definitely! We don’t want to move away from it in the sense we didn’t want to show it. It’s just we wanted to show that there’s more to his practice than only those works that he is notorious for.

Egon Schiele, 1890-1918. Standing Nude Girl 1914. Graphite on paper. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg. Image courtesy of Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg.

Egon Schiele, 1890-1918. Standing Nude Girl 1914. Graphite on paper. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg. Image courtesy of Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg.

CC: You mentioned before that Schiele was Klimt’s protégé. Are there any particular works in the exhibition where you can see Klimt’s influence?

TH: You can especially see it in his very early work, around 98 and 99 he was really emulating Klimt’s style. This was around the time when he was still going to the Academy in Vienna. He got bored quite quickly because he felt that the teaching there was too conventional, which is one of the reasons he sought advice from Klimt. You can see it in that he created these elongated figures with long draping cloaks, which bear resemblance to some of Klimt’s works such at The Kiss. But Schiele very quickly went a bit further than Klimt. He was really focusing on quite troubled looks for his subjects, and really exploring the structures of the body rather than just beauty.

Life in Motion: Egon Schiele/ Francesca Woodman runs until 23 September at Tate Liverpool, Albert Dock, Liverpool Waterfront, Liverpool, L3 4BB